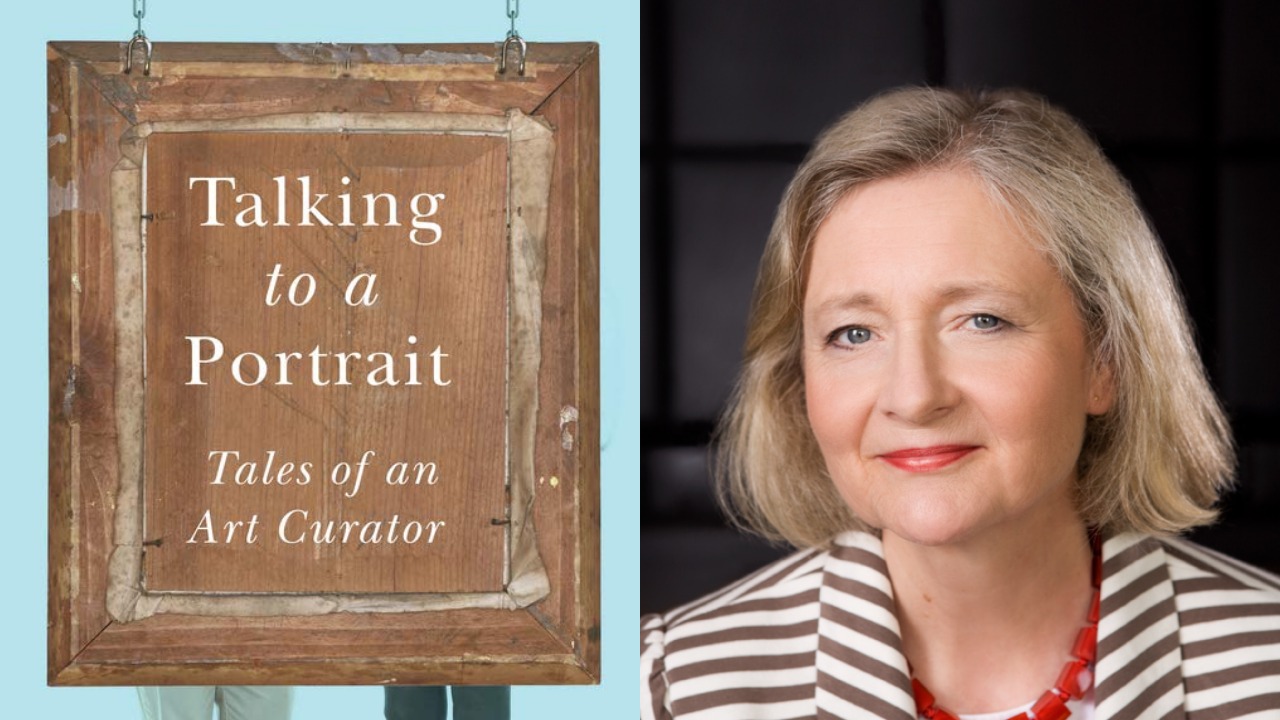

Talking to a Portrait: An interview with Rosalind Pepall

There are countless stories within the walls of an art gallery. You’ll find them in the brush strokes of a painting, in the dents of silverware, in the impressions left on a 1920s office chair. But any art lover understands that certain stories about the work on display also remain hidden from the public—either by choice or necessity.

Rosalind Pepall knows this well. For over thirty years, she worked at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts as curator of Canadian Art and senior curator of Decorative Arts. She handled artworks, objects and exhibitions everywhere from Montreal to rural Quebec to Europe. In Talking to a Portrait: Tales of an Art Curator (Véhicule Press), she details behind-the-scenes moments from her expansive career.

Pepall’s essays reflect her wide-ranging area of expertise. Quebecois readers will find her focus on celebrated local artists, from Group of Seven member Edwin Holgate to Montreal portraitist Jori Smith, especially compelling. But she carries a surprising depth of knowledge about more obscure objects, too, like a collection of 3,000 Japanese incense boxes. No matter the subject, Pepall’s exploration of the ins-and-outs of the art world—and what really goes down behind a museum’s closed doors—is candid and confident.

Chloë Lalonde: Talking to a Portrait is a collection of stories behind various artworks from the course of your career as a curator. How long did it take you to write the book? Were you writing as you were working?

Rosalind Pepall: I started when I retired from the museum. I found some of the writing I'd done way back, from when I was working on an exhibition. I had started writing about the people, the curators involved in the show—and I'd forgotten I'd written this. I had the book in my mind for a number of years, but I think I worked on it between four and five years, with other things interrupting along the way. I'd write two stories and then put it aside or do more research.

CL: Would you go home after your curating and write down your thoughts on the day's work?

RP: Not exactly. I was at the museum for just over thirty years, talking to people about the different things that were happening with the works of art. I found that the audience usually was so interested in hearing the stories behind the scenes: the collectors I'd met, or what might have happened during the exhibition, or what detective work I was delving into like acquiring works, or investigating the history of a piece. So this book was always in the back of my mind. I remembered most of these stories so vividly. But I did have to go back through the archives, the museum and past writings from my career to check on certain details. Then I sat down and wrote.

CL: Is it common practice for curators to reflect on their work in this way?

RP: Well no and in fact, what's interesting is with the pandemic, there’s a lot online now. There are the curators of the Frick Collection in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, our National Gallery of Art, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts—all of a sudden, everybody's getting online and talking about paintings and talking about their jobs. But when I was working on this, there really wasn't anybody talking about that. And still, it's not the same thing as just discussing a painting. You're really talking about the job and what you had to do to find out more about the history of the painting, about the style, about the artist. And you do do that, in a way, in academic work—that’s what curators write about. But I don't think that always gets to the public. I wonder how many people actually read the exhibition catalogues that we write from cover to cover. The idea of the book is that it will reach the average person who has an interest in art and just wants to know a little bit more about the behind-the-scenes. Often curators are very much in the background. People don't know what curators are doing all the time and the crazy things that happen to get a show up.

CL: You mentioned the exhibitions that have moved online because of the pandemic. Have you visited any?

RP: No actually, I have to admit that I haven't because we're getting so much online these days. I have listened to curators from big collections talking about a painting, but I’ve been to so many exhibitions in my life. And I even find that there’s nothing better than a rapport with the actual work of art. When you’re going to a show, it’s your own personal view of a work. You’re seeing what you want to see in a work without even knowing anything about it. I remember years ago when I was working on a historic site in Ottawa, they brought in this big curator from the States. And he said when you're looking at a chair, and you don’t know anything about it, what you do is you look at it very carefully. And you see how worn it is, or its shape, the colour, the texture. Before reading or researching anything about it, you should see how you feel about that work. And the same with a painting. What do you see in a painting without knowing who the artist is, without knowing what the date is? Just look at it.

That’s what people should be doing more and more, I think, is observing: watching and looking and making up your own mind about certain things. And then you start going into the history, Where did it come from? Where was it made? Why was it made in that shape? Why did that artist use those colours? And that's a little bit of what a curator does. You start asking all sorts of questions and in asking questions, it leads you down these roads that you never expected. And finally, you get some answers, or you hit blank walls, or dead ends. I try to explain that in the book, because that won't come out in your final writing [for the exhibition texts]—some of the mistakes you made or the dead ends, or the gossipy side that you can't really talk about.

CL: You wrote a little bit about how the word or idea “to curate” has recently been applied to so many different fields, like curating a dish or menu. What are your thoughts on the way the term is being used?

RP: The idea of curating is definitely trendy. In my book, it’s really about the traditional role of a curator as someone who is responsible for archiving and documentation, someone who is responsible for a collection and interpreting it, writing about it and doing research. They still refer to the curators of the Victoria and Albert Museum as “keepers.” That's what it really is: the keeper of the collection, the person who is supervising the collection. And so it has quite a different meaning. You don't talk about a keeper of meals, for example. I think they’ve stressed curators as more someone who designs and organizes, which is only part of what we do.

CL: It's almost like selecting a narrative, selecting the story.

RP: Exactly.

CL: How do you think the role of curator has evolved over the years?

RP: It hasn’t really. They’re still doing the same things. But social media has made them more effective in relating to the public, rather than just publishing a book or an exhibition catalogue that gets bought. Social media has made the relationship between the public and curators much more open and more public than it ever was. Although you always had curators who gave lectures while working on shows, they never really talked about actually organizing the show.

When preparing for an exhibition it's almost like a play in the theatre. You're preparing in the same way, you’re selecting all your objects and you're preparing to present it to the public. And then, when it's all ready, and you've done your research, and you've written everything, you've picked all the paintings and you've done all the loans and all the work that goes behind it, then it's time for the show. The curtain rises and people are critical about the show and how it was presented. But nobody really talks about how it all comes together. Who was involved? What were the problems? And why did you pick one work of art and not another? I tried to write about that aspect of curating.

CL: What is your favourite collection at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts?

RP: I love the Canadian collection. I like periods, and my period is really the late 19th to the early 20th centuries—around 1900, because so many things were happening. Different movements were coming from England and things were changing in Canada. They were trying to develop Canadian art at the time. The whole Arts and Crafts movement with William Morris, the Bauhaus artists and architects working, the French symbolists working. It's a very interesting period because it was the turn of the century and everyone was trying to prepare something new and different. I love the design collection too, though, and I worked very hard on it.

CL: Prior to the pandemic, what did your life look like and what does it look like now?

RP: Probably quite the same! Before, I'd be writing fairly regularly in the morning and then I'd go off and maybe do something at the museum. One of the big differences for everybody in the field now is that you can't get into the archives. While writing the book I was doing a lot of work in archives, reading all of Montreal painter Jori Smith’s letters and things. She became a good friend of mine and before she died she took me on a tour of the places she lived in Charlevoix County, Quebec, in the 1930s.

CL: Now that you’ve finished the book, how are you filling your time?

RP: I’m looking to my next project. I’ve always got a lot of writing to do. One of the nice things about lockdown is you’ve got the time to do it. I’ve also been reading my mother’s love letters from during and just before the Second World War. That’s a more personal project. I’ve got boxes here and I’m going through them all as I’m between big projects.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.